The New Theatrics of Remote Therapy

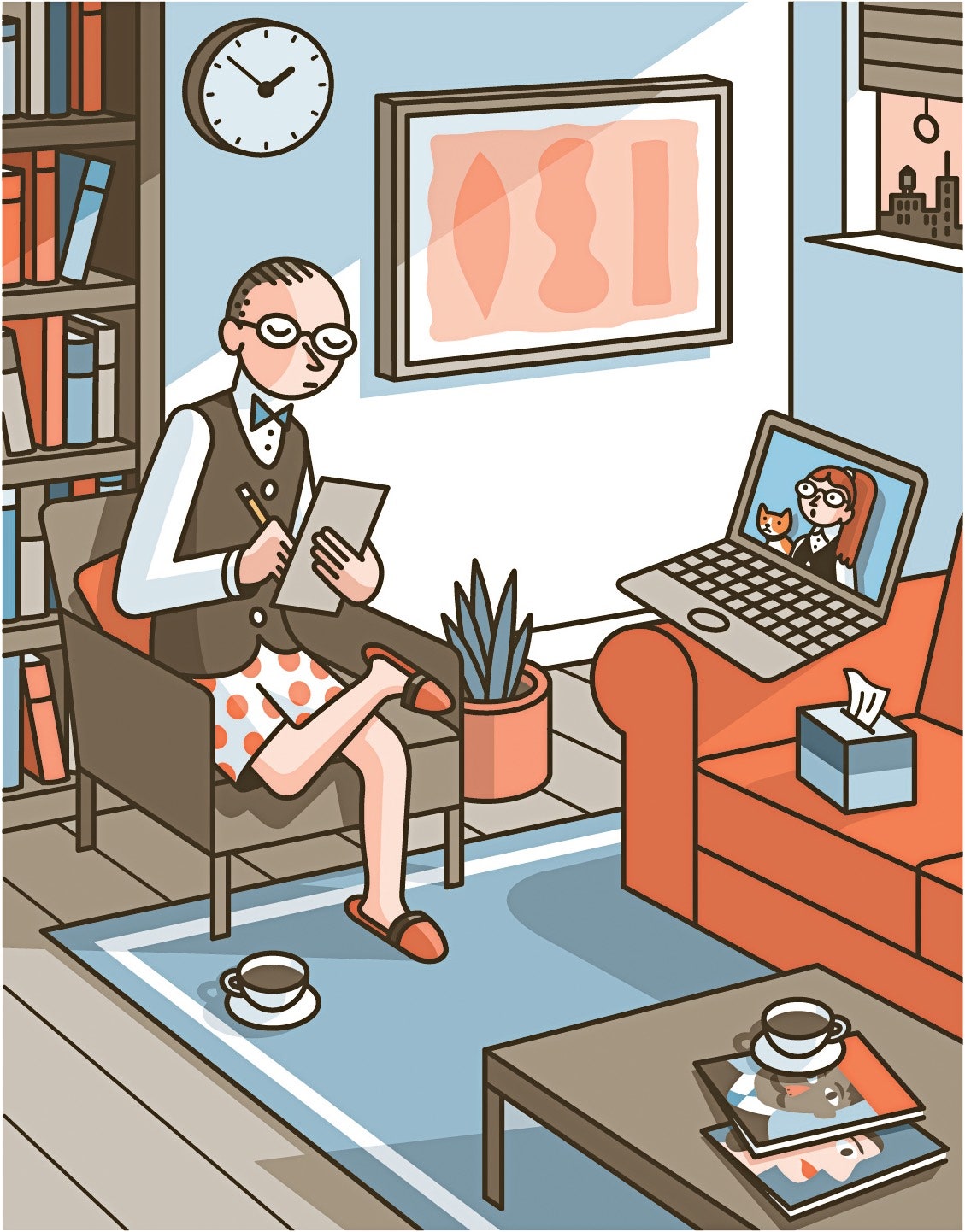

How does treatment change when your patients are on a screen?

Adam Gopnik

These days, the advice frequently directed at New Yorkers with deep-seated psychological difficulties is to stop having them. At a moment when every anxiety seems suddenly palpable, and every intimation of doom justified—“Congratulations on the prescience of your neurosis” is the suggested language of one therapist for patients who are obsessive hand-washers—it may seem indulgent to keep pursuing intractable dreams and dreads as though they were central to existence. Nonetheless, in the city’s great tradition, New Yorkers continue to seek out their therapists, millennial youngsters as much as neurotic elders. Governor Andrew Cuomo has launched a mental-health hotline, recruiting psychotherapists to provide pro-bono phone sessions for every sort of citizen. Therapy has become democratized: everybody needs an ear.

Despite vacant offices from the Upper West Side to Greenpoint, in the old haunts of classic Freudian analysis and in the newer clinics where a cognitive-behavioral approach reigns, the rituals of therapy go on. Several truths emanate from what might be called the empty-couch community. First, the new reality has altered the theatrics of therapy in ways that make both sides of the encounter aware of how much of psychotherapy is theatre to begin with. Second, after the day’s anxieties are digested, what remains are the same anxieties as before, newly energized by the crisis. And, finally, there are, in New York, concentric circles of psychic suffering: those at the greatest remove from the crisis are beset by anxiety that is free-floating yet intense; those closer to the epicenter endure immediate economic concerns that, at least for now, may occlude emotional ones; and then, on the actual front lines, where the doctors and nurses and hospital attendants work, a cry-another-day morale emerges, deferring trauma until it becomes impossible to repress. Various kinds of New York heads demand, as they always have, various kinds of shrinking.

“It’s utterly different and exactly the same,” says Barbra Zuck Locker, a psychologist and psychoanalyst who has been practicing on the Upper West Side for the past three decades. “We’ve been seeing a move toward remote sessions for years. We have a sense of having adapted to it already. I remember, though it seems so long ago, people talking just a few months ago among themselves: ‘Are you still going in?’ It was also generational—the younger people are much savvier. People called you up on the way to the gym and said, ‘Can we do the session during my workout?’ ” Locker has a soft, “r”-less New York accent and, in her combination of sweetness, solicitude, and sharpness, evokes Elaine May’s legendarily maternal psychoanalyst in the old Nichols and May sketch “Merry Christmas, Doctor.”

Like other therapists, the first thing that she mentions is not how differently she now sees her patients but how newly conscious she is of them seeing her. “Usually, I’m aware that my patients are largely looking down at my shoes, ” she explains. “And I’ve always made it a point not to have on what I call Maureen Stapleton shoes”—the heavy, practical kind. “But now they see only the top of the analyst, and you have to take care of your upper half. It’s sort of the Rachel Maddow syndrome.” (Just as viewers have speculated about what the television host is wearing from the waist down, clients wonder if their therapists are still half clad in pajamas.)

“I’ve gotten dressed and undressed more than I ever have,” another psychotherapist, Cynthia Chalker, says. “With my colors—I’m dark-skinned with short hair, have to be specific—I’m conscious of what shows up on me. ‘Does that green look O.K.?’ I check constantly with my wife.”

“I spent a day doing my work and I wasn’t wearing shoes,” the analyst Mark Gerald admits. But, he realized, “if you’re a psychoanalyst you know that whatever you are wearing or not wearing is somehow playing a part. We’re the people who believe in the power of the invisible parts of the iceberg. Anyway, some of my patients are actually staying on the couch while they’re on the phone. It was part of their commitment. So I put back on my shoes. Shoes were a way of honoring the work.”

The theatrical side of therapy has always been essential to its efficacy. “As therapists, we try to hold a frame—same time, same meeting place, same ritual—and holding the frame is hard in teletherapy,” Ricardo Rieppi, who works with Spanish-speaking clients, says. “There’s an embodiment that happens when you’re with a person. As therapists, we use our own counter-transference, our watchful, hovering empathy, to do our work. That’s difficult online. All the minutiae, my going out, meeting them at the door, their taking a chair or the couch—you don’t have that anymore. And I’m seeing the patients in their own home. One patient greeted me in an undershirt.”

We feel better because of the therapeutic scene we’ve just enacted, and as the scene changes so does the work. Gerald, who is also a photographer, is an expert on the significance of the empty offices. Last year, he published a book of photographs documenting analysts’ offices across the world. Hovering around his photographs is the possibility that the psychoanalytic imperium, already faltering in New York under the twin pressures of skeptical insurance companies and changing intellectual fashion, may, in the face of the pandemic, be coming to an end—with all those offices soon to be abandoned, like forgotten Egyptian tombs.

“I’ve been thinking a lot about the empty couch, ” Gerald says. “The psychoanalytic office is always a place of loss and impermanence. There are so many common factors, in terms of design. It’s a rare office that does not have a couch. A rare office that doesn’t have books in it. Rare not to have some kind of framed, non-suggestive art.” He points out that most analysts’ offices are tributes to Freud’s last office in Vienna, which was encyclopedically documented by a photographer just as Freud was forced into exile.

“A friend of his, August Eichhorn, enlisted a young Jewish photographer who owned a little studio, Edmund Engelman, to come to Berggasse 19 and photograph the birthplace of psychoanalysis. It was a risky thing to do—there was a big swastika over the building Freud lived in—and Engelman came in with a camera under his trenchcoat, as Freud and his family were getting ready to leave. Freud saw him, asked what he was doing, and when he explained Freud said, ‘Make yourself useful, take the passport pictures of myself, my wife, and my daughter.’ ” Those photographs of Freud’s office, unseen until the nineteen-fifties, the high-water mark of Freudian hegemony in New York therapy, became a template for every office after.

“There’s something very lonely and very sad about not being in one’s office,” Gerald says. “When the coronavirus came, I think people were struggling to find precedents in life: When else was the world like it is now? 9/11 and various parallels came—other times and places, going back to other plagues. But for an analyst one of the things that this brings up, strangely, is August breaks and vacations. Now it’s like we’re in this long, accidental August, one that no one planned, and with no Labor Day return quite in sight.” (read the rest here: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/06/01/the-new-theatrics-of-remote-therapy)

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.